I went to that small farm down a dirt road for months, convinced I knew very little and had much to learn. I thought I’d be able to call myself a farmer after I spent enough time learning from one. What I found, instead, was that farmer would introduce me to my last and final teacher: the plants themselves.

Read moreI Agree with People’s Worries Over Coronavirus

Following California Governor Gavin Newsome and Boris Johnson’s announcements of the ‘not lockdowns’, we thought it important that we wade through the myriad of issues that come with this pandemic. We in no way underestimate the seriousness of coronavirus and we absolutely DO NOT want anyone to go against the advisories in place. We want everyone to stay safe, and if they can, stay indoors. Here we are presenting a couple of things to be thinking through while you are doing what you can to keep from getting yourself and others infected.

Kindness/Cruelty

The UK government has been going on about how a key element of how we survive coronavirus is about compassion. Coronavirus really IS a test of how we treat each other. There are a number of digital communities arising to offer support to those who aren’t lucky enough to have friends or loved ones or have them nearby, and aside from getting involved in one of these groups, you can also exercise your empathetic muscle in an individual way. Check in with ALL your networks. Keep a regular and daily eye on friends, family and neighbours. If you know someone who is struggling, or could be struggling, don’t wait for them to ask for help. Not everyone has the capacity to reach out. Also, not everyone is a NEET or hikikomori.

What this pandemic is publicly exposing is who we are on the inside. The UK government is concerned that people are still going out despite the measures that have been implemented, and to be honest I am not surprised. Part of the issue is that we have been socialised to believe it is ok to put ourselves first at the expense of others, and that we have the right to do as we please without considering our impact. Now it is not as simple and straightforward as what I have just said of course, but the core logic is there. We CAN do as we please yes, but it shouldn’t be causing others harm in the process.

The Privilege of Staying Indoors

If you are a gig worker (for example Deliveroo or Postmates), domestic worker, in the service industry (in the US), homeless, a refugee, and/or suffer from mental health issues staying at home is not as simple or even possible. The reality is if you have a job for example in an office, have support from friends and family, and are free from harm of any kind, you can choose to stay indoors. Many countries have taken or are trying to take steps to relieve those who need to work to stay housed or fed. This may not reach everyone. Reach out to your neighbours, build alternative supply chains with friends, link up with relief systems in your city or town if you can.

At the same time, staying indoors can also be a different kind of dangerous. There have already been reports that domestic violence has increased with people quarantining themselves and similar issues have to be taken into account with any measures implemented and the kinds of support that need to remain available. In the case of the homeless, there was concern that the homeless would lose access to hostels as a result of social distancing measures, and while hotels are opening their doors to the homeless, there are concerns there are still not enough beds.

Branches of the Los Angeles Tenants Union have released demands that include the rights of prisoners to healthcare and safe shelter. Their demands remind us to think of the kinds of enforcement that are and could be further abused during this crisis. Undocumented folk should be able to have access to and seek healthcare without fear of arrest. People who are housed should be safe from eviction.

The Gendered Burden

The Guardian and the Atlantic both point out how it is assumed women will make up the majority of the slack because we’re all having to stay at home. This isn’t new sadly; countries expect free domestic labour from their feminine citizens. The least we can do as individuals is not expect the same from our loved ones. As it should be under normal circumstances, do not assume that staying at home suddenly means having free time, and do not assume that someone else, be that your partner or anyone else, will automatically take care of the things that need doing around the house. Your living space should be communally maintained.

Neonationalism

Shutting down travel and associating viral transmission with foreigners feeds nicely into the racists’ hands. The new powers of the police in the UK and increased military presence in other countries are how oppressive regimes start. I am not saying that the measures countries like the UK are taking shouldn’t be happening, but it can be a slippery slope. Your new neighbour is not your enemy. This is not China’s fault. This virus compromises weak immune systems no matter where you’re from.

Who Gets Access to What

In the UK, the government has covered 80% of the salaries of business they’ve asked to close and have nationalised the railways in an effort to keep the economy going. Sky News keeps commenting how unexpected it has been to see such a right leaning Tory government enacting leftist policies that were rejected just months before. This conservatives-talking-leftist is also eerily echoed in the States. Tax payment deadlines have been extended, and the self-employed currently have access to universal credit, employment and support allowance.

There is a lot being poured in to the British and US economies and supporting businesses, but who qualifies and how? And what do you have to do to access it? As previously mentioned, gig workers are still having to continue their jobs as the coverage they have access to isn’t sufficient, but even the provisions that have been allotted to owners of small businesses and companies come with specific criteria that may mean that many do not qualify. Larger businesses are already faring better with these loans supposedly for ‘small’ businesses. What has also come to light is the sheer number of people applying to access support is contributing to how long it has taken people to receive financial support. We also heard that banks are starting to reject the applications of some businesses but UK Chancellor Sunak announced changes will be made to the emergency aid scheme for small businesses. Only time will tell.

We’re Doing Communism

Well, technically it’s socialism since these are governments that are dictating precautions to people. But here’s the thing, we should be doing it. Mandates to limit exposure, collective ownership of healthcare, mass producing ventilators, smaller supply chains so everyone can get what they need are all things we need to do to protect each other. It is strange to think about how we’re conditioned to believe that an overly stocked shelf is a sign that everything is ok. Our needs as people, as cities, as states are actually much smaller. We don’t need massive box stores full of things that quickly turn into waste. Or shelves emptied because people can turn a huge profit from price gouging.

But, we also have to be careful about who we make compromises to. We have historically given away our rights to political leaders in times of crisis in exchange for ‘security’. It has not always been to the benefit of all. It can be socialism…but also fascism. A leader can nationalize production, call a halt on mortgage payments and issue a ‘stimulus’ but not give these to every person equally. A conservative government can suddenly start approving legislation that it once condemned. But a leader can present an open palm of relief to some and a closed fist to others. Be mindful of what your leaders not only offer you, but what they offer to those more vulnerable than you.

Taking Advantage of Paranoia

Speaking of mindfulness, think about how people share information with you: are they keeping you informed or driving you to panic? Are they giving you actions to look after yourself and those who are vulnerable or leaning in to your worst fears? This is a time when the predatory nature of capitalism will really hit you in the face. How reliable, for example, is Google’s recent offer to share people’s information to track whether they are adhering to social distancing or not? Elderly folks are warned to be wary of scammers who prey on their emotions, making them panic into giving away their money. We would all be wise to be wary of any business, news outlet, politician or otherwise who makes us feel that way.

Many people are made to feel like it’s their survival over yours. That doesn’t have to be true. China sent excess respirators to Italy. Cuba has sent doctors to five countries. A healer swears to heal all, no matter where they’re from.

The only way through this is together.

Interview with a Founder: On Queer/Mixed/Coptic-ness

This interview with Myriam was originally published on Coptic Queer Stories on January 27, 2020. It is shared here with their permission and edited to fit The Turn Left’s editorial guidelines. Use your imagination for what🍴, ⚱️and 👕 are stand ins for ;).

If you had one word to explain your relationship with Coptic identity, what would it be?

Up/rooted. An upside-down, rootless tree is the image in my head. I feel like I’m not rooted in it because of mixedness and because I’m not in Egypt. I find myself often realizing that you can’t really be removed from what you are though, right? That’s just a stupid frontal lobe illusion, like, “Oh haha, I’m not really what I am.” No that’s immutable, what you do with it I think is the important thing.

Have you always felt like this?

I fought so hard to belong. I was obsessed with it. I thought that identity meant that I had to reject certain parts of myself, and only express one part in order to be truly accepted by anyone. I didn’t understand people’s insecurity with me for a long time; and I realized that a lot of that was about me being more than one thing; they didn’t really trust me. My dad refused to teach us Arabic--well I should say that the reason he said he wouldn’t teach us Arabic was because, “Arabic is not our language.” Who knows if that was really the reason he didn’t teach us, but I always felt like I was looking at a group of people in a room with glass walls from the outside and I didn’t have the key to get in. All I’ve ever wanted was to join everyone else, to be a part of the group. And then I realized that fighting so hard to belong was like bending myself in uncomfortable and painful ways just to fit in, so then I ended up rejecting all of it.

Could you clarify what you think your dad meant when he said, “Arabic is not our language”?

He was referring to Arabic as it not being the original language in Egypt. We can call him an Egyptian nationalist, or more accurately probably, he was a Coptic nationalist. There are people, like my dad, whom I’ve heard say similar things, particularly many Coptic people in Egypt feel this way. There’s a lot of, “This is our land, we were here first” sort of thing, but with the history of Egypt, and the history of colonialism in North Africa, it’s tricky. Yes the Arabs were an empire, but the Coptic language exists because of the Macedonian and Greek empires, so it’s like where are we drawing these lines? But anyway, my dad would say, “If you’re going to learn a language, learn Coptic.” There was absolutely anti-Arab sentiment there.

Tell me about being mixed a little bit more. Tell me about your Italian half.

I’ve been thinking about that part a lot lately. I’ve realized that, in a way, my mother is mixed too. After dad died, my mom and I were traveling in Italy and I heard a lot of stories about her parents and how she was raised in the village. My grandfather was from Northern Italy, and Nonna was from Calabria. They called her il calabrese, which is basically calling her “the darky.” Apparently, everyone was afraid of my Nonna, I mean, rightfully so, she was terrifying. That woman saw some 👕. In Southern Italy, where she was from, it’s totally different; there's a much deeper, richer history of trade, integration, immigration, migration. I’ve convinced myself, without proof mind you, that Nonna was descended from pirates. But anyway, the only connection I had with Italy growing up was Nonna living with us until I was in junior high: Nonna making food, Nonna cursing in Italian, Nonna speaking broken English. Besides her, I didn’t live near either of my parent’s families, but we went to a Coptic church, so I ended up spending more time with Egyptians than with Italians. Italian culture felt very distant and much less tangible for me growing up. As I got older, I got this notion that I’m not only mixed, but I’m a mix of white and brown. Because Middle Easterners aren’t seen, by census standards anyway, as brown (societally they sure are), brown-ness seemed moveable in a way. All I can say about that is...Italians are wild. When it comes down to it, I typically just say that I’m Mediterranean; there are a lot of cultural similarities among all Mediterraneans. I don’t know if it has everything to do with the Sea perse, but every country that shares that coast has something in common.

I know you spent many years living abroad, could you tell me about your decision to live in the region?

I went to figure it out. In college, all of a sudden, I had to be something. At the time, the answers that I had didn’t feel sufficient, and it triggered an identity crisis. I was determined to figure that question out; what was I? I told myself that anthropology would give me the answer, anthropology was going to solve the problem of my mixedness. I just wrote a piece about this, how I felt like I could bifurcate myself and turn the white piece toward the brown piece and ask myself, “Why?” I felt like I had pieces within me that felt so outside of my own experiences, that I could just step outside of it all, to study myself and my people as if I didn’t belong to them. This came to a head when I moved to Egypt. There were times when cousins or friends would say that they were surprised that I wasn’t from there, that I blended in so well. But this is a thing that people say when you’re doing something that they approve of. And yes, I was doing everything possible to be approved of in Egypt because I needed to know I was Egyptian. I needed it to be confirmed by other people because I didn’t believe it, I didn’t think I was allowed to be it, I had to prove it. But at the same time, walking down the street was a strange game. One day, I’d be seen as a local like everyone else. On the next, I’d be an obvious foreigner, a target for harassment. Although every non-male body is subject to harassment on the street, I would find myself obsessing about why it happened to me. Was it because I wasn’t wearing a headdress? Was it the way I walked? The way I looked? Is my skin lighter after spending a lot of time indoors? I mean, I endlessly obsessed over figuring out the thing that signaled to someone else that I wasn’t a local. I think the part that frustrated me so much about that was the fact that it wasn’t up to me how I would be seen. That took some time for me to accept, but Egypt was where I had the biggest leaps forward. Going to the American University and working in different museums like The Egyptian Museum and the Coptic Museum, I interacted with folks on my own, without the influence of family. I didn’t live with family, and this helped me make my own relationship with Cairo; this was immensely important to me. Do you know that saying, “The stranger is blind?” The proverb, Alghareeb a3ma Walaw kan baseer. That was my guiding principle; it means that I am not going to be able to know what I can’t see. It amazed me how feminist nuns are, and they just are even if they’d never accept the label. I accepted, while riding in a car to Alexandria with my mentor that I was a feminist too. Egypt was where I realized I was queer.

Were these interactions with nuns something that was part of your studies, or were they self-directed explorations?

My aunt, my dad’s sister, is a nun. There were family visits on the first Friday of every month to her monastery. I owe my final queer awakening to an attraction to a female professor at AUC, rather than the nuns. For me, the realization was quiet and subtle. It’s always the professor isn’t it?

Tell me more about the language you use to talk about your gender and sexuality, and how living in Egypt at that time influenced these terms and identities.

I identify as queer: it captures both being non-binary and my sexuality. I am fine with any respectful pronoun, since I don’t feel any of them quite capture what I am. I’m attracted to people, not their packaging. I didn’t hear the word queer until after I’d had a soft coming out, and I figured, “Oh ya, that’s a lot simpler than my three-paragraph explanation, I’ll use that.” Since I was coming into my own without a queer community, I was figuring these things out on my own. I never felt comfortable joining a community and asking for acceptance. I just didn’t trust it because of my experience with mixedness and trying to be a part of the Coptic community. I felt like if I asked for permission, then I was going to burn bridges somehow. In groups of queer people, it seemed to me that I had a way of asking questions that would make people uncomfortable. People in those spaces seemed to be so protective and defensive, understandably. I don’t disparage anyone that, especially queer people, I just never felt like there was a space for me. So I collected bits and pieces of people that I met along the way, I’d read things and absorb them on my own. While it doesn’t really make me sad that this is the way it happened, it makes me feel it's important that those spaces are open to everyone, that I make a space for other queer people.

Do you still feel that way about queer spaces and groups?

It’s less about specific aspects of people, I’m just suspicious of people. Particularly in groups; with awareness, or a lack of awareness, people can be dangerous. It doesn’t scare me necessarily because I can tell the difference now between someone who is uncomfortable with themselves and me being uncomfortable with them being uncomfortable with themselves. That makes a huge difference to me. When I was in the Peace Corps in Azerbaijan (my time in lite imperialism haha) there were a few volunteers that were queer, some were out, some were not. By that time in my life I had an understanding of myself, though queer was not the word I was using yet; I had an understanding of myself as being part of that community. I remember these volunteers would say that they were gay first, then follow it up with their name and where they were from. Like “Hi! I’m gay,” all up in there with the rest and I remember thinking, “This is cool, but, I don’t know how to do that.” Plus, we were in a conservative, newly Muslim-led country, because Azerbaijan was under the Soviet Union, practicing religion there was illegal until the 90s. It wasn’t about religion, but as a womxn or someone on the female spectrum from a foreign country, people instilled a lot of caution in us. For example, if you were seen drinking or laughing in the street, we were told to expect that people wouldn’t trust us; that we were behaving in an “unbecoming” manner. Whether or not this was the culture of that country or if it was the Peace Corps’ interpretation didn’t really matter. The gender dynamics were constantly at play, and queer people were definitely encouraged to downplay themselves; their concerns were ignored and sometimes not considered.

It sounds like a tricky environment to navigate on your own. Can you tell me more?

I think as a first generation child, and a child of immigrant parents, the concepts of hiding and shame were pretty familiar. I was used to not dealing with so many things, and just tossing them to the backburner. I was used to operating under a veil of secrecy. By the time I was in Azerbaijan, I was like, “Ya, no big deal. I know how to do this; I’m gonna live my life in secret, it’s fine.” It was easy for me, but it’s only been as I got older that I asked myself why I was living my life in so much shame. I knew that being queer wasn’t something that I was ashamed of. And even though I tell myself I don’t think these things are shameful, when I go back to Egypt, I’m confronted with the fact that I am still indeed living with a lot of shame. I’ve grown a lot since the Peace Corps and living in Egypt in my 20s, but going back in more recent years, even after having done grad school and working in a variety of different jobs, I noticed that all of that growth seemed to go away. In Egypt, I immediately reverted into trying to fit into a heteronormative role.

Do you have a sense as to why that might be the case?

Even as a child, my internal voice has always said, “Don’t attract attention to yourself, you attract enough attention as it is.” It has always been in the back of my mind, and I know I’ve internalized, “Don’t stand out, keep your head down, don’t give anything away, do what is expected of you, you can find time to do what you really want when you’re in private.” Doing what is expected of you all the time makes it very difficult to understand what you actually want to do for yourself. Then it takes years to peel that behavior away. Going back to Egypt for a second time, I felt like I didn’t strive to belong anymore, so it was more obvious to me how much bending I was doing. Also, I wasn’t on my own like I was in my 20s. I was spending significantly more time with family, so smaller patterns became more obvious, and I didn’t really have as much of an escape.

Can you give me a quick timeline of the places you’ve lived?

I lived in Egypt from 2006-2007, then I was in Azerbaijan for the Peace Corps 2009- 2011, NYC in 2012, then I made my way to Thailand right before moving back to Egypt, where I was for the 2016 election up until recently. I’m based in Los Angeles now.

Could you tell me a little more about how it was living in Egypt the second time, especially around the 2016 election?

Getting most people to talk about politics before January 2011 was like pulling teeth. Some people were always involved, and talking about the need for reform; there was definitely an underground movement in Egypt for a long time, but generally people were afraid to talk, let alone protest. Now though, everyone has an opinion. These opinions are loud and aggressive, and I personally believe that most, if not all, people are suffering from some sort of PTSD because everyone has witnessed violence or lost someone to violence. Everyone has that story; families are divided by opposing political opinion. There’s a collective depression, and it affects people in different ways, depending on how they see January 25th and later taking down Morsi, who is now no longer with us. Plus, people are older now. Notions of patriarchy, heteronormativity, and so many other facets of culture can get more rigid with time. Even if they don’t like these ideas, as people get older sometimes old patterns of thinking resurface. I hope that I will not be that way when I’m older, but I’ve seen this with family members and other people that I know; it just reasserts itself. Somehow you end up renegotiating everything you’ve been taught as a child, you’re suddenly confronted with parts of your personality that remind you of your parent’s personality, “Do I become them or do I become something new?” This is a question that shifts with age, I think. The plan was always to go to Egypt for Christmas after dad died in 2014 because I needed to see everybody, but I decided to go early because I was in a terrible job situation in Thailand. My gut reaction was, “I need to get out of here, I have nowhere to go, I’ll just go to my family.” But just before I was supposed to leave Bangkok, I had this realization of, “Oh 🍴, I can’t be myself there, what am I doing?” You know as a foreigner in Bangkok, I was able to live pretty much however I wanted. But I convinced myself that it was okay, that I just needed to recover and that I needed to be with people that cared about me while I thought about next steps. But it was eye opening, to say the least, because I realized that I was less okay than I thought I was. It didn’t help that nobody was okay over there: they were not equipped to look after me or be okay with how comfortable I was taking the bus, for example. And not just the microbus, The Public Bus. They expected me to call the entire family for checkpoints along the way so they could make sure that I was still alive. Of course there’s always danger, though I can’t say with certainty if there is more or less danger on the streets of Cairo than anywhere else. Some places are always dangerous because of sexism, imperialism, classism, racism and other bull👕. No one can hide from any of that forever.

How did these daily experiences influence your goals of healing and recharging with your family?

Anytime I’d tell them about my terrible experiences in my work environment or with my boss, they’d basically just respond with a cavalier, “Ya, so? That’s life.” And while most of the time I’d have the presence of mind to respond with a, “Yes, but it doesn’t have to be that way,” it would get to me sometimes that they don’t have as many choices as I did. Without kids or a partner, I could move around with more freedom, I could switch jobs if I wanted to. It’s not like they could ever think, “Oh this boss is terrible, this boss is always on my case, this boss calls me at all hours of the day, this boss verbally and physically abuses me, maybe I will just leave…” They can’t. And they didn’t understand why I couldn’t just accept that reality. I ended up internalizing those perspectives, and it’s why I ended up staying in Egypt for so long ironically. I thought to myself, “What’s wrong with me? Why am I not strong enough to handle this bull👕?”

What I didn’t expect was that I would ever be able to talk about my queerness with anyone from my Egyptian side. I had pretty much determined that would be unsafe. There were even times where I’d freak out and imagine that if anyone found out, I wouldn’t be allowed around my nieces and nephews, that I’d be seen as some kind of virus, and that I’d be cut off from everyone--and that terrified me. There had been some tension in my family that existed prior to me arriving, but sometimes when there are problems and a new person comes in, tensions rise and that new person is blamed. I still don’t understand why an unmarried womxn in her thirties is so threatening to people. Honestly, it would be so much better if everyone didn’t see me as a womxn entirely! But people see a package, and being in this packaging, people assume certain things about my “usefulness” or my “value” or my “threat” because, depending on what color our skin is and what our bodies look like, we’re told that there’s not enough space for us, so we end up fighting for space don’t we? Most of the time I wanted to tell people, “Don’t think of me like a womxn, I’m not like that and I am not those things.” But that’s the struggle of gender, right? I wanted to tell them, “Gender is nonsense!” Because people can’t see how I see myself, they can’t see who lives in my mind. They just see my body, make their own assumptions, and then judge me. All I ever wanted to say to them was, “Listen, this is who I am, I am not a threat to anybody.” But if I said that then I’d be more threatening-- basically I was 🍴ed.

My mom, brother, and some of my other family members have known that I’m queer for many years, yet I couldn’t give my dad the chance to surprise me. I couldn’t risk the chance of him betraying me in that way; I couldn’t risk it, and I never did. There was an incident with a cousin of my father’s when I was living in New York, before moving to Thailand. My roommate cut my hair very short, and I posted it on Facebook. This cousin reposted it and made a comment, or rather, a crass joke, about Ireland just legalizing gay marriage. I confronted him and asked what that joke was all about, and he couldn’t give me a good answer. I told him, “I don’t know what you’re trying to say, but I don’t appreciate it. You don’t have that kind of relationship with me.” He took it down, but I could tell he was making an assumption about me, though he wasn’t willing to ask me the question or talk to me about it. He traveled to Egypt while I was there, so at some point I decided to confront him about it in person because there didn’t seem to be a way to move forward with that relationship without having a conversation. So, we went to some Americanish bar, those weird ones that they have in Maadi, and I bought him a tower of beer and I made him ask me. And by that I mean I told him, “You want to ask me if I’m gay.” When it came to discussing my sexuality and my queerness, or the shape of it, the experience of it, me going through it as a person, he didn’t want to know any of it. He just backed off. And though I thought it went down pretty well, in later conversations I realized that he didn’t actually engage with it. After that, I expected him to do the work for me, to gossip and tell as many people in the family as he wanted to, I didn’t care anymore. I thought that the people who want to understand me will come to me. Driving back with my cousin that night, I was surprised to have a really meaningful conversation with them. I didn’t expect anyone from the family to know me in that way, or be willing to know all sides of me, so that was really really meaningful to me. And that wouldn’t have happened if I wasn’t willing to sit down my dad’s cousin and say, “Look! What do you want to know, let’s talk about it. I’d prefer to talk about it instead of you being an ⚱️hole.”

Did you continue to have other meaningful conversations with additional family members after that?

There was one other cousin that I talked with, and I kind of just came out to her. My cousin pulled back into that same place of, “Okay, so what does that mean? No, I don’t accept this. I accept you but not this.” So I also pulled back and decided not to really deeply explain it; I just let her sit with it and decided not to put restrictions on her either. I figured that she can do whatever she wanted with that information, I just didn’t want to live with shame anymore. I don’t want to make it sound like if you don’t tell someone, it means your secret is shameful, but in my specific case, I didn’t want to worry about belonging to Egypt anymore. I realized that I was learning specific lessons from Egypt only, and the growth I was able to experience there had reached a plateau. Will I go back? For sure. But that feeling, that need to belong, is gone and I will be accepted on my own terms, as much as I’m untraining my mind to be accepted under other people’s terms. That will be a life-long unlearning.

Does it feel like you’ve closed the chapter with these cousins that you’ve come out to, or is there still some room for growth?

You know, who would have thought I could be all of myself? I didn’t know I could be; it only took a couple decades. Besides my dad’s cousin, no one else cited religious doctrine when disagreeing with my queerness. For multiple reasons I had decided not to tell my dad. We were all in Egypt at the same time for a cousin's wedding. I remember packing my bag when I heard some yelling; I entered the living room to find my brother and my father in a screaming match over the rights of gay people. The bible was being yielded as a weapon, there were hands doing threatening things, my mom was there just sort of distant, and my uncle turned to me and said, “I think your brother is confusing gay rights with civil rights, the rights of black people, he is confused.” And I just wanted to scream. I thought about coming out right then and there, “Let me give you all a real example to deal with.” But seeing how everyone wanted to yell and prove a point, their own point, it felt denigrating to hear them talk about who’s going to hell and who’s going to heaven. I knew it wasn’t my way. I’m not going to talk about who I am in order to prove a point, because it didn’t feel like it was about proving a point for me. I felt like, “This was my life.” My mom didn’t know it yet, my brother didn’t either--no one did. I don’t know, it didn’t make me feel safer--even though it seemed that I had an ally in the room. It didn’t feel safe, and it made me more sure that I wouldn’t be accepted by the people that I thought loved me the most.

Your experience is pretty unique in that you live at several different intersections. Do you feel any resolve about the Coptic piece?

At this point in my life, that part of my identity is pretty comfortable. I feel like being Coptic, queer, and mixed are all synonymous. It’s too old a thing for anyone to assume that Coptic culture has looked just one way for its entire history, or it has been one way the whole time. Egyptian history is ancient, there are things we don’t learn about pre-Nilotic culture or the Kushite (Nubian) pharaohs of the 25th Dynasty. I think queer people have been here the whole time, people need to accept it and make space for it because they can’t just keep pretending that we’re not here. They know. Seriously, gedos and tetas and someone’s baba know queer people on an individual basis. They’ve accepted it too, but they just don’t want to talk about it with each other. The pope is never going to say a good goddamn thing about it ever. It’s just a simple matter of accepting what you already see and being willing to understand. Whomever is willing enough, safe enough, privileged enough to be visible will make it easier for others who feel like they can’t be. And honestly, if you asked me about this a year or two ago, I probably wouldn’t have had this perspective. Nah, no way. Also, I’m not here to call out monastic culture to say it’s the gay haven, I’m just saying Egypt is the place where they invented monastism, or so we like to say. What greater example of fleeing the gender binary do you have? Of fleeing capitalism? I can’t assume a sexuality on an entire group of people, but that’s queer as 🍴. Isn’t queerness not only what we do with our bodies, but also what we do with our minds? It’s how you see yourself, how you see other people, and how you love people. In Egypt, homosexuality has been practiced by so many tribes and cultures, like the Bedouins, since ancient times up until the present. Emperors went there for lovers (that’s a whole other story), they’ve memorialized them in statues; it’s just a matter of forgetting what you know or what our grandparents refused to acknowledge. I think it’s safer for some people to deal if they think of the world like this; if the world is determined a certain way, then things aren’t shaky and you are not responsible for your choices nor do you have to think about things too deeply. Personally I find it more comforting that everything is changeable and everything is mutable. Nothing is new.

You know, I never thought I’d be in this situation, telling my story. How could I imagine that this platform would even exist? I have to say, it is timely, and we are brave and beautiful.

If you had to go back in time, what would you tell 15 year old Myriam?

I’d tell her, “Take your time.” Listen, none of these realizations came to me easily. If you have the privilege of space and time, take it. Be patient, love yourself, especially when you feel like you fall short. That’s definitely something that’s big for me--it always will be. We are not all born queerly confident. I’m still getting there, and so will you. If you don’t have the privilege of space or time, you need to find support. Find a book, a youth center, PFLAG group, GSA, chat room, Tumblr, I don’t know anything for 🍴s sake. Or maybe just hop in a time machine and come find me at The Turn Left; I will always listen.

Tell me more about your organization, The Turn Left.

The Turn Left is a forum for discussing ideas that better integrate the economy, society, and environment. The idea is to build on that space by having conversations with people from all different walks of life, to find ways for those three things to complement each other better. Then, eventually, we’d do those things in practice, and sustain ourselves instead of asking other people for money. The idea is for us to be a closed loop example of what it means to be a whole world instead of sacrificing many for the growth of some. We published a piece by Salma Mustapha Khalil called, “A Woman’s Place,” which is about public space in Cairo and how women and people on the feminine spectrum are limited in their access to it. This was written in response to an incident a few years back when a woman who recorded a man accosting her was shamed for exposing the harassment.

Has being queer influenced this project?

Sandra, the person who I started this with, and I met in Cairo. She had the idea years later, and came to me with it, and we realized that this is how we would keep ourselves sane, motivated, and grounded. The name came to me because I had just read This Bridge Called My Back, where Gloria Anzaldúa talks about the left-handed world, the world of possibility, the created space outside of conflicts. We don’t want The Turn Left to be an exercise in thinking about how to dismantle things, we want it to focus on how to build new things, a perspective Tannia Esparza showed us when she shared her piece. How do we build a world that teaches people to see others as they’d like to be seen? How do we build a world that isn’t divided by 7 billion different types of binaries? I’m disturbed by how much conversations come to, “Ya things are terrible and there’s nothing we can do about it!” How do we imagine beyond that? How do we not recreate hierarchies? How do we not bring the same bull👕 from heteroland into queerland? How do we build that for ourselves and for those who come after us?

How can people find The Turn Left and The Desert Salon?

Find us at www.theturnleft.org. We’re open to submissions. We’re also @tturnleft on Twitter. Take a look at the people we’ve talked to and at some of the discussions that we’ve had to see if you’d like to contribute. Also, we have our Desert Salon now--it’s a monthly radical discussion space where we learn together. We discuss everything from the imperialist/capitalist/heteropatriarchy to local water prices. One of the things that we hope is to build a community that takes joy in and relies upon one another. We want to help build lasting relationships where folks can exchange ideas like in the salons of old; creative, political, or otherwise. It’s just a simple act of making a physical space that’s open, safe, and reliable. For now, we’re located in the Antelope Valley in California, but I’m hoping to grow it eventually.

I’m curious, have Coptic people taken notice?

I dream and hope to have them in it. I know that people are curious, yet tentative. This is the way I’m seeing myself and the Coptic community now: the drawbridge is down. I’m not running away from anyone anymore, I’m not rejecting where I came from or who I am. Come find me, I’m here. I’ll be here, and I accept that people might come to me in their own time, as I come into myself in mine.

Why would I ever want to be one of them

"Manzanar Split Tree"by thereshegoesagain is licensed under CC BY 2.0

In anthropology, they teach you to recognize patterns of human behavior. Many like to believe that it’s the science of human beings. That with its tools, we can make sense of humans. All I found was that we are animals doing performance art.

It’s also the science that helped Armchair Victorians answer the question: brown people, why? I didn’t see this you know, as a child. I didn’t see that anthropology was my way of chopping myself into pieces and turning the white piece to the brown piece to ask the same question.

Why?

Last year around this time, I was on a road trip. It was eye-opening in many ways. We visited ghost towns, old mining towns that had either run dry or were barely hanging on. Places ravaged and plundered by the reckless pursuit of natural resources. I never really processed that people still lived in these places and willingly called them ghost towns. Descendants of settlers, miners, or people trying to buy cheap property to cash in on tourists like us. Like me.

I don’t always feel brown, you see. Most of the time, I don’t even really allow myself to think about my own brownness. It’s never really been up to me. In the ghost towns of Nevada, I was brown. The stares told me so.

But the stares weren’t all meant for me. I was traveling with two older women, people who I considered new friends at the time. One, a tall gravely-voiced woman who gave no shits. White. The other was a smaller, wiser woman who also gave no shits, in her way. Black. Police cars drove by repeatedly. Groups of children came out to wave…and stare. There was ‘no room’ in the fancier hotel. I felt the stares on my back constantly. It made me furious.

If you had asked me at the time why I was so angry, I wouldn’t have been able to say. It’s not as if I haven’t felt that gaze before. Remember: I don’t allow myself to think about my brownness. Later, speaking with the smaller friend, the one who bore that gaze every goddamned day of her life, she told me something I hadn’t considered: they probably thought I was her mixed-race kid.

I am a mixed kid, of a different mix. It’s been my bane and my greatest strength. In those towns, some still thought it was a crime[1].

On our way back from Nevada, we stopped at Manzanar[2]. This was the site of an American concentration camp during World War II, two hours from where I grew up. I can’t really explain to you what I felt there, but the suffering will poison that ground forever. You can see it in the trees.

The taller one kept talking about how if we’re not careful, this country would put people in places like that again. I replied; this country has never stopped doing that[3].

I am back in that town that I grew up in, two hours from Manzanar. These days, Adelanto is only an hour away. Make no mistake, it’s a camp like any of the others. An ICE Processing Center they like to say. But I know what that means. Somewhere in your bones, you know it too.

Why have I not allowed myself to think of myself as brown? Because somewhere in my bones, I know what happens to brown people. The question that haunts me now is why would I ever want to be one of them? The ones who decide who’s white, brown or otherwise. The ones with privilege. With power. With the perceived superiority over others by virtue of crushing them beneath their boots.

I think I also tried to be an anthropologist to ask: Why do you do this to us? To my father? His people? My friend’s people? My neighbor’s people?

I can finally answer that question without anthropology. Because you forgot you are one of us. There’s more genetic variation in every other creature on this earth than there is between human beings.

We were all brown, once.

“I’m not interested in pursuing a society that uses analysis, research, and experimentation to concretize their vision of cruel destinies for those who are not bastards of the Pilgrims; a society with arrogance rising, moon in oppression, and sun in destruction.”

– Barbara Cameron “Gee, You Don’t Seem Like an Indian…” from This Bridge Called My Back

[1]More on Miscegenation laws in the US https://www.thoughtco.com/interracial-marriage-laws-721611

[2]https://www.nytimes.com/2018/07/07/us/manzanar-japanese-americans-internment-camp.html

[3]More on the relocation of Native Americans: https://www.thoughtco.com/the-trail-of-tears-1773597; On the prison industrial complex https://www.nytimes.com/2018/01/18/us/new-jim-crow-book-ban-prison.html; On profiling and surveillance of Muslims https://ccrjustice.org/home/what-we-do/issues/muslim-profiling

When discussing abortion…can we highlight poverty?

The root of the abortion debate is a joke; it is political garbage that masquerades itself as reasonable evidence and invokes a passionate divide on both sides. It does this to perpetuate the issue without ever solving the “need” for abortion. Now, before you continue to read this, know that I am not here to take either of those two sides, they ignore everything that in my opinion could actually point to a solution. The reason why such a complex issue has been simplified is not that either side is right or that there is a cookie cutter solution to this social issue.

In either case, I’m not going to discuss the making of these two very decisively worded labels. Instead, I am going to discuss how mainstream feminists continue to disregard the minorities that they should be fighting to protect.

That’s right, I’m going to talk about those liberal “Nancys” who continue to ignore the role of economic inequality in abortion. It's not always a race issue, but the numbers show intersectionality between income and race is a huge factor when it comes to abortion. There needs to be a push to minimize the abortion stigma to create a learning culture.

Global economic inequality is pro-choosing for you

Let's start by looking at some sources that define poverty since that is what I will be using to make this point.

Based on this, there is an issue with using the federal definition of poverty because it is influenced by the World Bank which considers extreme poverty as, well very extreme… meaning that they take into account only those who have $1.90 or less to spend on a daily basis. It has not adjusted for cost of living increases or how the face of poverty is changing. For this argument, I will only be taking into account the United States because it would be difficult to obtain the numbers on global economic inequality.

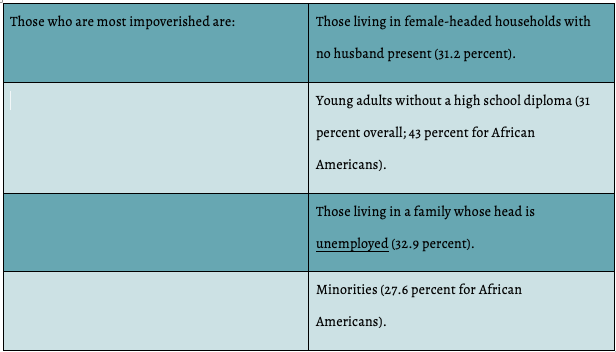

What are the numbers of people who are struggling on a daily basis? Well it is difficult to determine, as discussed in The Changing the Face Poverty in America, because there are a few things that need to be taken into account such as wealth distribution, how poverty itself changes over time (mainly as things become more accessible), cost of living relative to income in a specific period, and the way poverty can be discussed in the context of the time. Poverty now looks different than in the 1950s. Here are some examples of what poverty looked like in 2011.

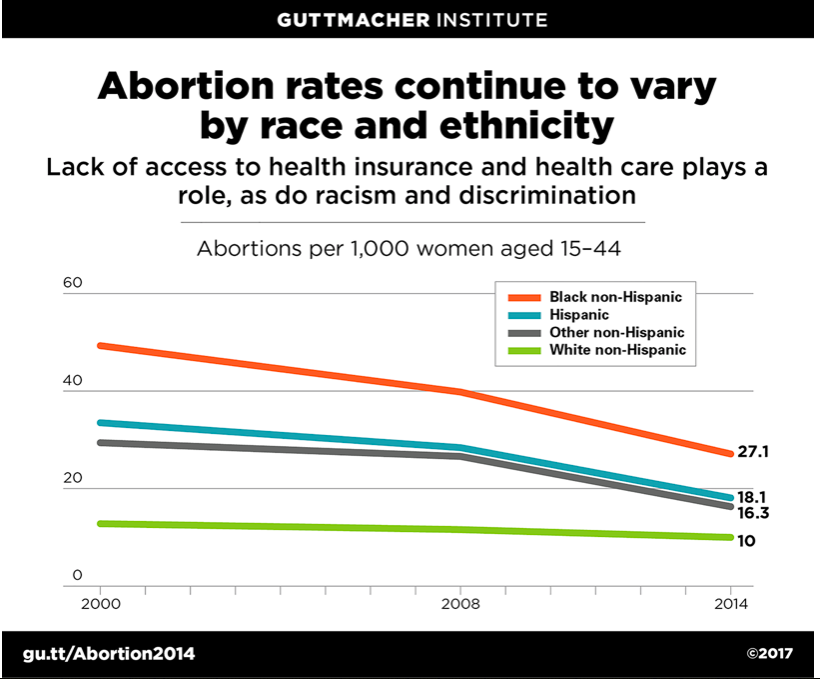

Women are being influenced to choose abortion because of a lack of economic wellness. To quote the Guttmacher Institute:

“…the abortion rate among poor women remains the highest of all groups examined in the study, at 36.6 abortions per 1,000 women of reproductive age. Abortion has become increasingly concentrated among poor women, who accounted for 49% of patients in 2014.”

At a national level, the United States is witnessing extreme poverty being eradicated. Poverty is still there, it is simply changing. As long as this divide in which 31% of female-headed households or that more than 59% are African American, Hispanic or Asian in impoverished conditions, there will be single mothers of color who do end up considering abortion largely because of their economic disadvantage.

Pro-life does not allude to pro-living

When it comes to how income inequality can become a factor in an abortion decision, pro-lifers also aren’t faring that well. Pro-lifers’ choices often get in the way of others’ opportunities to gain economic wellness.

Current voting trends for pro-lifers favor conservatives who include abortion restrictions. These same conservatives, however, also favor economic strategies that perpetuate an income divide. By choosing to lower taxes on the top 1%, conservatives aren’t giving CEOs incentive to hire more or spread their wealth but rather increasing government dependence on middle-class taxation. Not only that but conservative policies also tend to reduce social programs that assist people in poverty.

There is a disconnect between the policies of conservatives and their demands on pregnant women. There ends up being a disregard of how economics can push someone to choose abortion. Those who are choosing to abort because of their personal economic status do it because they cannot guarantee a reasonable lifestyle for another child. I say another child because often they are already mothers choosing to abort. As the chart above highlighted, 55% of those having abortions are already mothers.

Addressing the historical context of abortions

In order for abortion to become less stigmatized and discussed fairly, there needs to be a separation from Margaret Sanger. Sanger has already been given more credit than was due: she founded Planned Parenthood and coined the term “birth control.” She is seen as respectable by “Nancy” liberals because she paved the way for facilities that focused on women's health and placed them in areas where people were not being “served.”

Ever noticed that you will find Planned Parenthood buildings concentrated in, or around areas with communities of color? In fact, a closer look at Margaret Sanger’s life reveals she held white-supremacist, eugenic beliefs that mixed into her life’s work.

After all this time her beliefs still have consequences. Remember those earlier stats? Abortion rates are higher in African American than white communities, even though they are a smaller group.

While Sanger might have had good ideas like highlighting women's health, freeing women from the burden of constant childbirth, educating people about contraceptives, those ideas are continuously overcast by her twisted intent. She was not fond of African American communities and believed their population should be controlled. As such, there is a need to be distant from her when discussing abortion because she was wrong to believe in racist discrimination. Likewise, Sanger’s inclusion makes some pro-lifers feel justified by her track record of enforcing beliefs on others. She doesn’t deserve the glory of a civil rights leader, thinking ahead of her time. She was specifically a product of her time.

During Sanger’s life, there was a social crisis where women were having illegal abortions in unsanitary conditions, dying from them or having seriously damaging consequences. Sanger was equally a product of America's eugenics craze where groups of people who would later have the power to decide who could have children erroneously believed that whites deserved to choose who to sterilize. As a product of her time, she should stay there. If you’re a disheartened mainstream feminist well, let me give you an ignored woman of science that maybe you could look into instead: the mother of the double helix, Rosalind Franklin.

We should take Sanger’s good ideas she had to offer society as a whole as starting points for us to continue the advancement of things like educating on parenthood for all genders; allowing women to have a right to their bodies and be able to use contraceptives at their own discretion, to be informed of them; as well as understanding the economic cost of bringing a child into this modern society.

Addressing both sides

True pro-choicers would not stand for these economic divides; they would rally to mitigate impoverished conditions.

Those who stand for current economic conditions aren’t protecting a woman’s right to choose but rather satisfying themselves with the tools that continue the need for abortions based on poverty or fear of it.

True pro-lifers would not be willing to pass on impoverished lives to newer generations. Instead, they would rally to fight off those conditions which have women consider the idea of an abortion. Pro-lifers who allow intergenerational poverty not only expect people to crawl out of it unscathed but also bear the economic responsibility of more children. They aren’t caring for ‘potential children’ but rather inflicting their belief onto others without any self-restraint or benevolence.

Whether you are a pro-choicer or pro-lifer, you would benefit by rallying together and trying to mitigate poverty to reduce the number of abortions needed because of lower socioeconomic status. Pro-choicers must realize that abortions done as a result of poverty are not done by choice because, I can assure you, nobody would want to choose poverty. Pro-lifers must realize that if they are going to enforce their personal choices on others then they too must make that commitment to quality of life.

Sources:

https://www.debt.org/faqs/americans-in-debt/poverty-united-states/

https://ourworldindata.org/poverty-at-higher-poverty-lines

https://prospect.org/article/changing-face-poverty-america

https://www.guttmacher.org/infographic/2016/us-abortion-patients

https://www.guttmacher.org/report/abortion-worldwide-2017

http://time.com/4081760/margaret-sanger-history-eugenics/

https://www.guttmacher.org/infographic/2017/abortion-rates-income

Kindness/Cruelty, Morals/Ethics: What We Tell Ourselves and What We Tell Others: Part 1

When I was a child I was told a great many lies, some by friends and family, others by society at large. Part of the reason I have a grudge against Disney is because they sold me a lie that it took until my 20’s to recover from: “Some day my prince will come.”. Society even supports this lie by saying “there is someone for everyone”, seeding the sense of inadequacy that develops from failed relationships and a lack of relationships. The sense of inadequacy that companies and marketing campaigns use to sell you things, and society blames you for, while ignoring that their messages mainly target white women and tell men they also don’t have to do anything as a partner will magically appear.

In anime the latter LITERALLY HAPPENS…but I can’t seem to find a gif for it so -

Now before I go all Fight Club on you (ha ha, get it? Cus satire?), the point I am making here is that we are raised with conflicting messages, messages meant to soften the full body blow that is the world we live in, maintain us as productive members of the social unit, and leave us imagining that even in a zombie apocalypse, we’ll all hold hands, pitch in, and make things work.

Or not.

The other reason the above gif works is because just before the events it depicts, Robert Carlyle and his wife were sat at a table having dinner with an elderly couple who had let them and a few others hole up in their house to protect themselves from the zom-sorry, those infected with the rage virus. They were trying to ‘make it work’. On that note, another lie I was told was that kindness is always repaid. What was built in my little mind in contrast to the stark and later bleak reality was the idea that the universe always rights itself, bad people are punished, and good people are rewarded. The universe DOES right itself, our definition of ‘righting itself’ however is wholly human (individual even) centred, and what we forget is balance in the universe does not necessarily mean balance for US. Anyway, the notion that all will work out the way we want in the end is part of the trick that keeps society functioning and the point from which I would like us to break things down: kindness/cruelty, morals/ethics, the lies we tell ourselves and the lies we tell others. To make things a bit easier to follow we can imagine that on the one hand we have kindness/cruelty and morals/ ethics, and on the other the lies we tell ourselves and the lies we tell others. They all overlap, because the lies we tell ourselves and others are often about kindness/cruelty and morals and ethics. In short, we tell ourselves lies about how kindness, cruelty, morals and ethics function in the world to keep ourselves functioning in the world, and we tell others lies about those same things in order to keep both ourselves and others functioning in the world. Thus the web is spun.

So going back to the example I opened with, children get sold the idea that they will eventually find love, marry and have kids. In addition to sparing children the harsh reality that it may not turn out that way or could possibly turn out that way but unhappily so, adults feel like ‘good’ people for shielding children and themselves from the idea that maybe, but not absolutely, unhealthy relationships are all that lies in store. Because society has trained us that being alone is bad or means there is something wrong with you, so heaven forbid you wind up ALONE (cue scary reveal music). Also, it is assumed that if you are alone you are not helping to perpetuate society by HAVING CHILDREN, which is the other, more basic reason children are socialized to marry and have children.

So back to kindness/cruelty. We are all raised to believe that people are inherently “good” or kind and that when you are in trouble, someone will always help you. We believe in the Good Samaritan, the kindly bystander. What we ignore is that they are the exception and not the rule as our notions of good, bad and normal are in reality constantly shifting. Part of this is because ‘good’,’ bad’ and ‘normal’ are terrible words, empty in meaning and excellent place holders, and part of this is that as place holders they are filled with a general, but not mutually agreed upon understanding. They can mean everything and nothing at the same time.

A good (ha ha) example of the issue with kindness/goodness is a form of the bystander effect. While training volunteers in Egypt to work against sexual harassment, a trainer showed a video of a crowd on a train platform in the UK. The idea was to show the volunteers how mass mentality works, and argue why it could work to stop harassers in public spaces. A group of actors had been hired to enact a pick pocketing to see how non-actors would react. The actor very obviously took the other actor’s wallet out of their pocket with the latter pretending not to notice, and in the video, it is clear that non-actors noticed, but no one said or did anything. Now we all like to imagine that if in that situation, we’d stop the pick pocket, but we know in our heart of hearts that is just not very likely. To be clear, I am saying UNLIKELY, not IMPOSSIBLE. We are more likely, as a second reenactment of the pick-pocketing showed, to do something when someone else does something first. This brings up the notion of discomfort; people are not comfortable in the moment of the situation when faced with ‘do something’ and stand out or ‘stay quiet’ and follow the crowd. At the same time, we do not like the idea that we are more likely to follow, or to seek permission to do something in public, or that maybe we just don’t care, so we tell ourselves that we are not that person, and that if a stranger needed help, we wouldn’t hesitate to act. Here’s some more proof for you.

But then this was the issue when it came to sexual harassment in public spaces: bystanders rarely if ever ACT, and they were even siding with the harasser. What the volunteers were being trained to do was change the flow of the tide so that more bystanders than not would stop the harasser versus support them or blame the harassed.

These kinds of issues also unfold in more personal settings. Take the classic example so common that if it hasn’t actually happened to you, you have most likely seen it in your favourite tv series: a woman goes to confide in her friend that she is being sexually harassed[1]. She is visibly scared, but her friend, instead of comforting her, asks her if she was sure what she experienced was harassment. The friend then proceeds to downplay the story, suggesting to the woman that maybe there was some sort of misunderstanding or surely the person didn’t mean for their actions to be perceived as harassment. Congratulations: here is a lie we are telling both ourselves and others. We do not want to shatter our belief that the world is a ‘good’ place filled with ‘good’ people, we do not want to see our friends and family hurt, and we want to impart that utopia to our friend through convincing her that maybe it didn’t happen the way she thinks it did, and urging her to go back to the mental state she occupied before the incident(s) occurred. In peddling this fiction, we are reinforcing a social norm that promotes toxic masculinities and femininities, and we are shielding ourselves from the idea that terrible things may happen to us and our loved ones, or that we may be the perpetrators of acts that cause others pain. The reality however is that we are all guilty of causing pain, and it is only when we face this reality head on that we can begin to take apart why we do these things, how we can change, and maybe how we can heal the wounds inflicted on others and those visited upon us. Then maybe reality will seem less terrible, and we won’t want to hide ourselves and our loved ones.

I could delve into these ideas further but there are too many things to unpack that would take us down many many side roads and into early retirement. Mainly what I was aiming at here is to get us thinking about how we could rethink what we do and how it impacts our own lives and the lives of those around us. Don’t be the silent bystander. Read your children the original Grimm’s Fairytales or stories where the princess saves herself (I am ashamed to admit I don’t know any off the top of my head, but I suggested Grimm because at least the prince loses the odd limb or gets derailed from his quest making it a bit more realistic). Take your friend at their word when they tell you they’ve been harassed/assaulted (I’m frowning at you Jussie Smollet.) Next time, I will try to tackle morals/ethics. Wish me luck and bring paracetemol. I’m off to watch the Promised Neverland.

[1]In this hypothetical the women is indeed being sexually harassed and there is no ambiguity. If you are wondering what defines sexual harassment you can read Gunilla Carstensens 2016 piece ‘Sexual Harassment: The Forgotten Grey Zone’ and/or watch the BBC clip ‘Is This Sexual Harassment’ (https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p06x0jv5)

Daring to Dream: Reflections on Mothering and Social Justice with Love

I spent three summers buried under wet sand thanks to Armida, the old school Xicana who met my mama while she waited tables at La Cocina de Tere and quickly became one of the handful of women who raised me. Armida taught me about floating. And beach sun. Sandcastles and living on boats and salty air in your hair. Side ponytails, and brown coppery lipstick-growing up Xicana by the sea. The last summer we spent together, Armida got sick. I was four when I had just learned the ABCs song in English and I couldn’t wait to sing it for her. I practiced the song all the way to her house. But when I walked into her room...her small body covered in white blankets, her voice soft, her eyes still loving, she was barely there. I knew it would be the last time I’d ever see her. I never sang her the song, no words to describe the feelings that come with endings at that time. Armida died. To this day I know I grew up Xicana by the sea because of her.

Four years ago, I was excited to participate in a circle of love called the Transitions Labs, a growing community experiment from the Movement Strategy Center asking many of us to ponder what we, as people living in this current moment, want to plant now to harvest 100 years from now, 1000 years from now, 10,000 years from now? The question has ebbed and flowed in my body ever since and while I’ve been doubtful of many things during my time alive, the only thing I’ve ever been certain of is my dream/wish/calling/commitment to be a mother to Xol one day.

Of course raising a child does not guarantee the survival of the best humans can offer. We ask ourselves overwhelming questions like...Is it audacious to think that what I can do now can be useful in 10,000 years? Will humans and life forms, as they exist now, even be around in 10,000 years? Or, what kind of something is important to plant if I will not be the steward of those seedlings? What responsibility am I passing onto someone or someones hoping they too decide it’s worthwhile to keep growing?

I always return to gratitude for having heart and thought partners to feel through these questions because they’re thoughts worth “moving at the speed of trust” as many in our movements say. Perhaps these aren’t so much doubts, but more of an attempt at loving, self-reflective accountability for actions taken now that will inevitably have ripple effects for our kin in near and far futures.

These thoughts aren’t unique. Many brilliant hearts and minds have been asking the accountable, courageous questions for a long time. Octavia Butler, wrote worlds and struggles and strategies into existence in her prolific writing interventions. I’ve been deeply touched by Adrienne Maree Brown, who has made huge offerings through her collaborations like Octavia’s Brood co-edited with Walidah Imarisha and her book Emergent Strategy, with tools, lessons, reflections and delicious footnotes for us to try, highlighting, among many nuggets of wonder, the ways nature “organizes” to survive. Our social justice movements are experimenting with old and new strategies approaching our current political moment with creativity and love. On Mother’s Day 2018, Southerners on New Ground (SONG), a regional Queer Liberation organization in the South, led “A Labor of Love: Black Mama’s Bail Out Action”.

The action, led by organizers, family members and loving community, released 30 black mamas and caregivers in the thick of money bail systems that for too long have targeted and preyed on working class people of color. SONG addressed the devastating racial and gendered impacts of growing U.S carceral systems on black mamas and black people in a collective action that changed the “flowers and cards” Mother’s Day Holiday into a platform for love and change making. Black Lives Matter and #MeToo have taken us on journeys, leveraging celebrity platforms, grounding us in the power of direct action and reminding us of the power that STILL lives in storytelling. In Brooklyn, New York, a small loving team of queer women and people of color bicycle riders started BiciNinxs, a summer cycling camp for brown and black girls ages 8-12, offering a space to learn how to ride, build, and maintain a bike and care for each other. @cycle.bici raised 5K to run three camps with over 20 girls in Summer 2018 funded through a grassroots fundraising campaign! These efforts seemingly large and small are all HUGE. Whether the work is largely visible or seen only in our homes, down the block, at church or at the farm, many are believing in an us now, and building for an us tomorrow.

I don’t know if Armida knew the impact she would have on my life. As I honor her memory in the simple mundane acts of humaness she offered, creating the most joyful glittery aspects of my childhood, I think about the ripple effects we experience in our short lifetimes and wonder if maybe what we can pass on as future ancestors, lives in the lessons offered to us everyday in the complex contradicting simplicity of being alive. Armida loved me. Made a home out of sand and ocean water for both of us to live our joy. Her love is not a social justice movement that everyone knows. But in my childhood riddled with harsh and trauma, her love WAS justice. Her love, like the love that grounds our movements and inspires us to keep trying even and especially when we fail is what deserves our awareness and thoughtful attention. It’s the reason I dare to dream about parenting.

Becoming a mother to Xol one day is bold in this time of such hurt. To have these dreams, commit to them, and do is the work of believing. Trust. The work of love. I write about Xol, speak of and to Xol often. I used to think I needed to keep Xol to myself, like uttering their name would spoil their arrival, but they came in a dream almost a decade ago and named themselves (They/Them is pronoun I use on purpose as I would like to support Xol in deciding how they want to be gendered.) I know now Xol is an ancestor returning, an ancestor I’m welcoming into this world with words like I do with veladoras and cempazuchitil flowers on Dia de Los Muertos for our dead. The more I speak of them, the more they become.

The world I believe in and love is like the baby Xol I believe in and love- I’ve never seen or touched either of them, but I’m committed to being part of the dreaming, plotting and loving that brings them both into existence.

As we begin 2019, I’m setting intentions to continue this parenting/world dreaming in conversation with loving community.

Below is a list of writings, guides, podcasts, and brilliance that has continued to help shape these thoughts and held space for courageous questions:

● How to Survive the End of the World Podcast

A Woman's Place

Culture plays a very big role in how we understand public and private space. Where I come from, for the most part, private space is a myth. In Egypt, we find pride in our social nature. We love the fact that our homes are always open, our tables are always welcoming and our spirits are mostly high. In our culture, we celebrate coming together for feasts, for birthdays, for funerals. And for revolutions. However, this hospitality rarely extends to the public space – to the street. Culturally, and sadly, a man’s place is in the public space while the private space is the woman’s, to exist in but not to rule or control.

Then there is the political side. Recently, we’ve lost the ability to be so social. Even if we don’t count all the friends lost and relationships that broke over the political rupture we’ve gone through, it has become risky to exist in big groups in public. Demonstrating is illegal and in a legal system where everything is poorly defined anything can be deemed a demonstration. And ever since the crash of the Egyptian pound, private gatherings are simply unaffordable. This break in how we’re meant to live our life, how we understand our existence in the space we inhabit has broken us – well, dented us. My generation has already been battered and had their blood and bones splattered on the very streets we now have little access to. Demonstrating much other than our miserable individuality is highly frowned upon. We are a living manifestation of divide and ruthlessly conquer.

Public space is also, of course, gendered. For men, the public space is the street; for women – the public place is her life. Our (in)ability to walk down or stand on the street is a consequence of women being perceived as the object of observation. We are constantly under scrutiny for the specific purpose of judgment – by everyone - including, most heartbreakingly, other women. When does she leave her house? What time does she go home? How often is she out? Who does she go out with? Where are they likely to go? What is she wearing? Answers to these questions are to be known, by neighbours and the infamous bawab (doorman). Then, if you pass that impenetrable filter of respectability and honour, and are about to get married, how you inhabit your personal space is now next on the list. Can she cook? Can she clean? Does she take care of herself, or does she let herself go once nobody is looking? Is she a pretty-matching-PJs kind of girl or wretched hair-don’t care kind of girl? We live for the gaze, and practice existing for it, even in private.

A while ago, a girl was standing on the street, in suburban Cairo (not that this should be relevant), when a man approached her and invited her for a cup of coffee. He claimed to only want to relieve her of the harassment she’d get by simply standing there, and that he was “not bothering her”. Her response was that he was in fact bothering her. She then posted the 30 second video on Facebook and it blew up… in HER face.

Initially, most people were hung up on the man’s mispronunciation of the name of the café where he suggested they go, and completely disregarded the intention of the video. He’d just invaded her personal space and had used her own inhibitions against her. Yet, he became a public figure as a victim of unjustified shaming. She, on the other hand, was declared as deserving of his minor trespass - and the shaming that followed, given the way she was “probably” dressed. She wasn’t actually visible in the video, yet, reposting Facebook photos of her in short dresses claiming “She was asking for it” was seen as perfectly acceptable, deserved even. The argument about her clothing is that she “dresses like a European, so she should accept this supposedly European behaviour” of being asked for coffee by random men on the street; “it’s not like he verbally abused her - or worse”.

The consequences of these 30 seconds were fame for the man and complete desecration and isolation of the girl who lost her job, her reputation and even some friends.

There are no social rights for a woman in Cairo. There are only responsibilities. She is responsible for her own reputation, as well as the reputation of the men in her life. The way she behaves is instantly a reflection on the men that she is associated with - father, brother, husband and, very quickly, son. Hence, the rush everyone is in to shut down her ability to self-express. A girl, we’re told in school, is a direct expression of the morals of her entire family. She is also an expression of where the entire society falls on the moral spectrum.

In the debate against the girl, people attacked her for shaming him. Her morality was reduced to not caring about another human, despite her own position of vulnerability against him. There were also debates on whether she had a good reason to be standing on the street to begin with. She put herself in harms way; as if harm is inevitable – and sadly, in Cairo it is. That same argument was used against protestors killed and injured in police attacks – why were they there? It seems to be the way we perceive the world in Cairo: harm is inevitable and it is our responsibility to get out of its way – fighting it, eradicating it, is not an option.

Once her own images came to light, a miserable twist occurred; people blamed her for her own misery. While his reputation deserved saving, hers was everyone’s property to do with whatever they wanted. The way she dresses was seen as unacceptable – skinny jeans are an abomination, and hence, anyone is entitled to attack her. She was portrayed in long posts as this demon that is out to destroy the lives of innocent men just going about their days by being a walking sin. In fact, someone claimed she was lucky someone was nice enough to offer to get her out of harm’s way – or rather stop her from being harm to other people, by simply existing in that space.

This brings us to the religion argument. Islam calls for modesty. A woman (and in fact a man) should always be modest in the way they present themselves to the world. Dress decently and – more relevantly humbly. A woman should not be a point of attraction. One argument against our fellow Egyptian woman was that she dresses attractively; hence she is inviting and should bear the consequences of her decision to draw eyes to her. These arguments dismiss the elements of that very religion that also demand, all of us, men and women, to cover our eyes from what we feel is too revealing. Again, the responsibility – of both man and woman – falls solely on the woman. Shortly after the incident, and another one involving the murder of a husband defending his wife against a harasser, Al-Azhar declared that harassment is haram (forbidden) in Islam, regardless of what the woman is wearing.

The main aspect of this situation with which I’m struggling the most is the amount of women that not only rushed to the rescue of the man’s reputation, but inhumanely and with painful certainty shattered the girl’s. From where I am sitting, seeing a video like this, all I can feel is admiration for her bravery at holding up a camera to a man approaching her on the street and not letting herself be paralysed by fear at what he could be capable of. She is not oblivious to the existence of plenty of people like him who would rush to his side and attack her; yet she proceeded to post the video online anyway. I would be terrified and I was and am for her. I still catch myself, after years of living abroad, scanning the area around me and making sure there is always safe distance between me and the next man on the street; that is after finally learning to walk with my back straight and pretend to be comfortable! Look straight as opposed to the ground and not speed up frantically when someone walks close to/behind me for some time.

I have been wracking my brain, trying to understand or relate to how someone who walks the same streets I do, who witnesses the same things I have witnessed can completely break a fellow fighter-for-mere-existence like that. But then I remembered. When the declaration by Al-Azhar came out and after some discussions with friends about its possible value, it hit me. We have internalised this responsibility; it has gone so deep in some of us that they have managed to wear their adjustment to these conditions as a badge of honour. For those who are familiar with The Handmaid’s Tale, they’re the wives of Gilead, who are proud of their share in the oppression and use their place to abuse other women who practiced their freedoms.

I flash back to a time where I would cover up to leave the house, like it wasn’t about the street, like it was my decision, like my body cover is the way I should be, it is my invisibility cloak that will get me from point A to B without drama. I remember dismissing the incidents where it didn’t work. I remember seeing girls who dressed up and looked nice and simultaneously thinking they were making things harder for themselves while picturing what I would be wearing if it were up to me. And this is what I think it might all come down to – us thinking it is not up to us. It is up to society, to culture, to religion what we wear and how we exist – and society, culture and religion all tell us to exist in the way that makes life easier for men. Be ugly on the street and sexy at home. Be everything and nothing all at the same time. Saving our best for our husbands and choosing to follow the religious instructions because they are meant for us, to protect us and to make us worthy. Sound familiar?